My fatal flaw as a writer is the fact that I'm an editor. On a computer, in a word processor, the mutable pixels prod at me. I have to fight myself — my editor-self. It's as if, for him, words are only created to be cut. And on a computer, he has the advantage. The arrow keys and delete1 are so accessible. It's hard to compete. It's too easy for him to win.

My best writing happens when I am fully present, when I'm not thinking about revision. But on a computer, I get caught in hellish loops, revising the paragraph I just wrote instead of moving on to complete the page. I oscillate between the past and the future, wondering whether what I've written is good enough and where I'll go from here. I'm robbed of the present.

After losing many bouts with my editor-self, I've learned: sometimes, in our slippery, modern world, the only way to access the present moment is through time-travel. Thankfully, time machines exist. I have one, and it only cost me $300 on eBay.

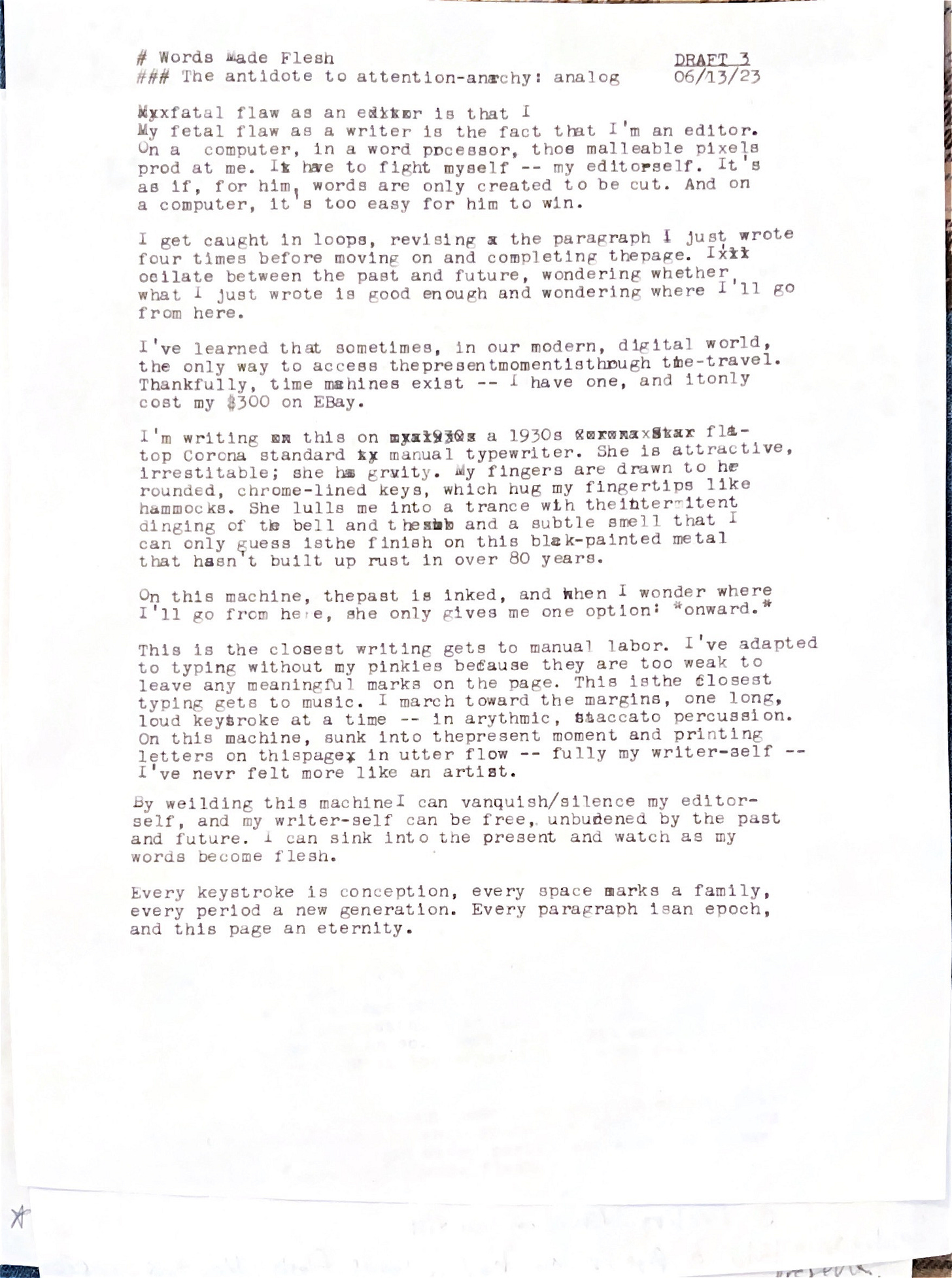

I'm writing this on a 1930s flat-top Corona Standard manual typewriter.2 She is attractive, irresistible; she has gravity. I'm drawn to her rounded, chrome-lined keys, which hug my fingertips like hammocks. She hypnotizes my editor-self with a bell and her subtle scent, which I can only guess is the finish that has kept her rust-free for over 80 years.

On this machine, the past is inked, immutable; and when I wonder where I'll go from here, she only gives me one option: onward.

This is the closest writing gets to manual labor; I only use my pinkies for Shift because they're too weak to leave any meaningful marks on the page. This is the closest typing gets to music; I march toward the right margin in arrhythmic percussion, one long, loud keystroke at a time. On this machine, I sink into the present moment and stamp letters onto a page in utter flow; this is the closest I've ever felt to my writer-self.

These words are safe from my editor-self. I create them in a moment in time, in a fleeting state of mind, while focused on a single line. These words are created and can't be cut. Every letter, every word is immediately made flesh. Every keystroke is conception, every space a wall between two families, every period the end of a generation, every paragraph an epoch, and this page… eternity.

Springboard:

What is this slippery, modern world robbing from you? Is there a grippy, analog tool that could change the outcome?3

Before editing this on my computer, I wrote three drafts on my typewriter, with ink and paper. If you’re curious, here’s Draft 3, which inspired to get her own typewriter — a bright-orange beauty. Check out her essay about it: “Bang, Bang, Now You’re Mine.”

Somehow, I just realized that the labels on a MacBook’s keyboard are in all lower-case, and that bothers me — even more of a reason to use the typewriter!

There are two writers I admire who inspired me to make this purchase:

, with his typewriter essays, and Van Neistat, who scripts all of his movies on his Corona Standard.This slippery-grippy dichotomy is from David Kadavy’s idea of “grippy” and “slippy” tools, which is featured in his book, Mind Management, Not Time Management.

I agree. And writing with pen and paper is even more directly linear and forward moving!

This modern world is robbing me of my time. My complete reliance of being on my phone through all times of day is robbing me of hearing my own thoughts. So much of my time is consuming others content as it is increasing accessible to do so.