On day 29 of my summer in Iceland, I finally made it to the wildest corner of the country: the uninhabited Hornstrandir Nature Reserve. This place is too far from Reykjavík for casual tourists or puddle-jumpers, and the only available mode of transportation, after arriving by ferry, is your own two feet. I considered my first month of backpacking as merely training for this leg of the trip; all the hiking, hitchhiking, busses, and ferries had been to get me here. The people who make it to Hornstrandir are after an adventure.

It was a cool and cloudless morning, conditions I'd learned to savor. So, I was outside on the deck of the ferry for most of the one-hour ride from Isafjördur's harbor to the tiny dock in Hesteyri. I spotted a couple squads of puffins flapping their short wings like engorged humming birds, which wings were able to keep each squad-member hovering about three feet above the water as they returned to their burrows in one of the sheer cliffs of the many massive fjords.

We docked, and I made my way to the trailhead out behind the Old Doctor's House, which was boxy and white with green trim, surrounded by purple and yellow wildflowers. Someone called my name: "Garrett, hæ!" I turned to see the somehow unsurprised face of Grímur. It had been a week since we were neighbors in Monkey's backyard, and he was about to lead a group of ten hikers on a multi-day journey. I glanced at the group of families dilly-dallying as they packed their gear, drinking hot cocoa around a picnic table, and I was grateful for the moment that I was solo.

"It's so nice to see you," I said as I shook Grímur's hearty hand.

He pushed up his glasses and said the same.

"I'm going to do that six-day route we talked about, and I'll end in Veiðileysufjörður," I said. "You think we'll cross paths at all?"

"Likely no. We're going straight to the bird-cliffs. And we'll take the ferry out of Hornvík."

"I consider it a good omen running into you," I said. "I hope to see you again."

"Enjoy this beautiful day!" Grímur replied before returning to wrangle his group.

I had been anticipating this moment all summer, or really since birth. As I hiked up the hill beyond Hesteyri and as Grímur's group shrank into the distance, I was finally free. Sure, I'd been hiking alone for a month, and I'd ventured out into the wilderness. But not like this. In Hornstrandir, I was without cellular service; I was 30 miles from any road or any vehicle with wheels; I was alone on the trail; I was at last unencumbered and inaccessible to the world. This vision of freedom had allured me — What could be more pleasurable than to gaze long from a mountain ridge between two fjords and to see no smudge of humanity whatsoever, to be held privately in the naked lap of Mother Nature? And it had deceived me.

The trails in Hornstrandir are mere footpaths — scarcely marked, lightly trodden — and there are only a few small areas designated for camping, marked with A-frame wooden outhouses that conceal gravity-powered toilets, each with probably 36 cubic feet of capacity, which were thankfully also mostly empty. It's illegal to camp outside the permitters of these few sites, because the land in Hornstrandir is reserved for Nature. Each campsite is nestled in a fjord, and each one is about eight miles from the next. I was happy to have these shorter days, and I was in no rush.

I stopped early, on the mountain above Hesteyri, to sit on a log and meditate with a soft gaze — half the time facing back toward Hesteyrarfjörður and half the time facing Aðlavík. I bent my back over the log so that the crown of my ball-cap was pointing straight down; the whole sky was below me, and I was leaving the ground.

It was only 3:00 pm when I arrived at the Latrár campsite, and there was a group of four men there who were packing up to leave. They were all rising seniors at San Diego State on a one-week trip. I complimented them for choosing to spend their time in Hornstrandir, and I asked if they had tried to hike up to the Latrár Air Station. Before they left, I learned that they had turned back because the hike had been much longer than they'd expected. I thought, That's because you're encumbered by each other, and probably soft — unlike me. It was 3:00 pm, and these little boys were just starting their day of hiking. Of course they were! The day was still young; the Sun wouldn't set for another three weeks.

I had two options: (1) go for a walk on the beach, read, and have a meal to end a leisurely day or (2) double the day's milage by doing an out-and-back hike to the long-abandoned Latrár Air Station atop Mt. Straumnes. But only one of those options would support my burgeoning identity as a hardened outdoorsman.

The first two hours of the hike were steep switchbacks, and by the time I reached the top of the plateau, I could no longer make out my bright-orange tent against the grass; it'd shrunk to something smaller than a pixel. The next three hours were a gradual incline toward the far edge of the NY strip–shaped mountain. I could see my destination but had no idea how many miles remained. As I approached, clouds filled the valley on the far side of Straumnes, and the plateau became a sort of peninsula, surrounded on three sides by a sea of wet air.

The Latrár Air Station is an abandoned American radar outpost that was operational from 1958–1960 during the Cold War. There, U.S. airmen would monitor the airspace in the Greenland–Iceland–United Kingdom (GUAK) Gap to detect, shadow, and police Soviet aircraft. After those two years of operation, it was shut down for its high operating costs and the logistical challenge of its remote location. It has since been abandoned. The remaining property was handed over to the Icelandic government and then overtaken by Nature.1

It was June 30, yet the decaying concrete buildings were filled with mounds of unmelted snow, each conical pile with a crusty top-layer that insulated the rest. There were two uneven rows of these broken rectangles, the smaller and fewer buildings to my left seemed like barracks, and the more uniform buildings to my right seemed like offices that were once filled with state-of-the-art equipment and American airmen working to deter nuclear war. There was one road that ran between the two rows of buildings. It drew me north with a subtle magnetism. At the end of the road was a large, circular platform where the radar bubble once was. And beyond that a gray void unending.

I followed a trickling stream to the edge of the cliff, over which it poured without a sound and disbanded into the cloud-carpet that had rolled in from the horizon. It looked thick enough to walk on, thick enough to catch me.

Perched atop that thousand-foot drop, I did not fear falling but fantasized about the freedom of flight. How would the dense fog feel as it slowed my body hurling at terminal velocity? Would there be enough drag to place me without a splash into the veiled ocean below? Or would I free-fall forever and never have to face the jagged shore? I did not want to die, but I felt an urge to jump. I saw a gull bank up and over the precipice, and I reminded myself that I can't fly.

The symptoms of confinement are universally dreadful — the world closing in on you, limiting you: a bird in a cage. And those symptoms are amplified in solitude, hence the punishment of solitary confinement. But this was the first time I'd considered the symptoms of freedom — the world cracking open in front of me, inviting me: a bird without a nest. These symptoms only present in certain moments of overreaching: getting too close to the heart of things, getting too far from society, becoming a little too doubtful of the fragility of myself. It is in these moments that all is silent enough and I am close enough to hear the call of the void.

Don't you ever envy the dead for their wisdom? What they must know about the nature of reality! They must know exactly what I am incapable of knowing, the ignorant living.

I did not want to die. Maybe the void wanted me to, or it wanted to see if I would. It was inviting me. But I am free. It is not immoral or irrational or ungrateful for me to hear the call, but it would be for me to accept it. And I could not deny it either. I had to answer. Ultimately, the call of the void is life-affirming. For in that moment, I held the rest of my life in my hands and gave it as a gift to myself by answering: No. I took a step back from the edge and tipped my hat, like a gentleman declining an offer from a lady of the night: "You are beautiful, enigmatic, even awe-inspiring, but I am married to life and will continue living."

My descent was faster, easier, more solid, less foggy. I came back to the ground, and it wasn't until the moment before I fell asleep in my tent that I felt finally mortal again.

I awoke on what I did not know would be the start of two entire days of solitude. I would hike for 16 miles up and over the crests of three fjords, and I would not see or hear another human. The only macroscopic organisms I would encounter would be the insects that would leap from the low-land marsh and the birds that would soar straight over me and into the proximate glacial valley.

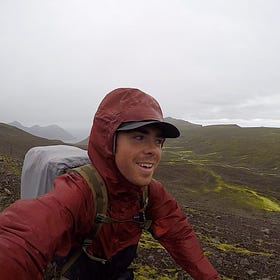

After three hours of steady-grade hiking in steadily stronger winds, and then thirty minutes of steep snow-hiking with my feet and knees bowed out at 45 degrees to lower my center of gravity, I crested the ridge out of Aðlavík and into Fljótavík. Before me was nothing and everything I'd ever wanted. Fljotavík was a short and stubby inlet for the thin bridge of land that was both a beach and the bank of a lake; Fljotavatn was wide and stretched deep into the valley, filling the space between this ridge and the next with a lush marsh. On the ground again, I marched through the mud for two miles, toward the tiny red outhouse marking the Fljotavatn campsite, set in the back of this U-shaped valley.

The only spot for my one-person tent was a raised semi-spherical mound of dirt and grass that was dry but not level. Streaming down from the bowl-shaped part of the fjord was a waterfall, the sight and sounds of which soothed me as I napped and wrote in my journal:

Unless someone shows up here, which I doubt will happen, this will have been the first time in my life when I have gone a full day without seeing or talking to another human. And it's pretty odd. I've enjoyed it, but I know I wouldn't want complete isolation for too long. . . .

I was just lying here thinking about how nice it will be to have visitors. Taylor will be here in 11 days, and I'll be with her for 8 days. Between now and leaving Iceland, I'll be with visitors for 20 days total. That leaves a little under 40 days remaining solo.

My alluring vision of solitary freedom had included the act of outdoor self-pleasure. I was motivated by the novelty of it. And on the morning of my second day of solitude, I decided to exercise my right to privacy. It was the early morning; if anyone were hiking to the campsite, they wouldn't arrive for hours. No one was around for miles, yet I didn't strip to the nude. Instead, I exposed myself through the flap of my underpants. It was cold, and all I could imagine was that someone might crest the fjord and gape at me through a pair of neck-hung binoculars or a long-lens camera. It was a novel experience, to have my seed caught by the flora of the fjord. It was liberating but debilitatingly so. In the very next moment, I realized that my unconscious motivation had been to distract myself from the loneliness by feigning connection. I had deceived myself.

Hiking alone is entirely different than hiking with a partner. The physical risks I didn't find so troubling. It was the psychological, existential toll of solitary freedom: having no one to ground me. Ecstatically alone in nature, there was no real way to distinguish my experience from a dream, besides to remind myself that I had slept the night before, that I had woken up that morning, that I was in fact mortal. The least illusory part of reality is other people; without eye contact, conversations, handshakes, I was less assured of my existence. But with that illusory feeling came a rich confidence, for there is no reason to fear in a dreamworld. There is no way to die. On my second day of solitary hiking, I breezed through the hardest terrain of the entire summer: a snowy near-vertical rock-scramble that I climbed like a ladder for forty feet before landing in the saddle of the mountain ridge.

Fog had fallen into that low nook, so there was no view like there had been above Aðlavík. I couldn't see the next cairn, much less the fjord I was about to enter. And I paused to revel in it. This sweet solitude! A dome of the world all my own — my self, tiny and obscured. I thought about staying there forever, or at least until the fog cleared. But I worried that it would make me unreal. Instead, I sat in silence and breathed for a while before continuing, toward the ground again.

The weather carried on like this all day, and it wasn't until I descended into Hlöðuvík that I could see. The sky hadn't changed — still dark; I had just snuck out of it, under it. I arrived at another deserted campsite, another empty outhouse: Knock, knock. No answer. I boiled some water for dinner and tea and then started to pace around the campsite, dark and misty. One lap, two laps, three laps. . . . Four? Suddenly — "Hey!" I shouted, waving from my shoulder with my entire left arm and smiling with my mouth agape. "Hi! Welcome!" I must have startled these strangers because I started running at them, Hans and Evelyn.

"Hey, how's it going? I'm Garrett. Where are you from? Did you enjoy your hike? It's your first day here? Sorry the visibility was so bad for you today. . . ." There I was clamoring for connection by talking about the weather, after spending weeks trying to escape the dreadful parts of society, among them: small talk.

"The hike was beautiful," Hans said. "You know, there could've been a blizzard. It could have been snowing all day. So, the clouds weren't a bother. What we were able to see was beautiful." Hans had immediately made the weather deep, and I'm not sure I could have accomplished that with an entire year more of solitary thinking. It had shut me up, and I was still again. Once Hans and Evelyn had settled in, we sat together for tea and became friends.

Hans and Evelyn are an unmarried German couple, ages 59 and 60. They looked like two towering steeples on either side of the entrance to a cathedral, for what they seemed to have between them is divine. Both of them had healthy gray hair and were as fit as I. Hans and Evelyn are both architects and have many other talents between them: painting, sculpting, carpentry, sailing. Their trip to Iceland would be most accurately classified as retirement planning. Hans plans to buy a sailboat at 65 and traverse the globe, with Evelyn joining at least for parts of it, and the two of them were visiting Iceland to see whether it is worth adding to the Retirement Sailing Trip itinerary. Hans and Evelyn have known each other for 42 years but have only been romantic for a decade. It seemed that neither of them had ever wanted to get married, but for all of those years they had wanted to be together. I recognized them as fully individuals and fully partners.

Before going to sleep in his two-person tent, Hans went to bathe himself in the river on the border of our tiny beach-side campsite. He stripped to the nude before wading in and washing himself with fresh snow-melt, as if there were no one around for miles.

It is easy in the world to live after the world's opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.

– Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Self-Reliance"

Springboard

A carefully crafted question to help you dive inwards:

What parts of yourself do you conceal from the crowd?

This was Chapter IV in a five-part series about the 81 days I spent trekking through Iceland, called “Feeling Fire & Ice.” You can see the series’s contents here. Next is “Stillness & Ambition.”

Thank you for reading,

Stillness & Ambition

I needed to sleep so that I could dream. I needed to dream so that, later, I could achieve.

While researching the Latrár Air Station, I found a veteran-run organization celebrating the memory and preserving the legacy of these American radar stations: US Radar Sites Iceland. There are hundreds of photos from the airmen who served there, and they give you a great sense for what life was like atop Mt. Straumnes. For instance, this photo, which has the following caption: "During the winter it took 2 CATS to go up the mountain. One to plow. The second pulling the sled."

…have you ever seen the old documentary ALONE IN THE WILDERNESS…one of my fave documents https://www.aloneinthewilderness.com/ …i have dreamed of such loneliness before but know it untenable for me in the real world…was cool to hear and see some of your journey into the humanless realm…