Last night, you had many dreams. The only question is whether you recalled them this morning. The same is true every night and for all humans, yet we don't discuss dreams. We resign them to our unconscious and dismiss them as "not real." Well, here's another point of fact: last night you mistook your dreams for "reality."1 And in that way, we are all a bit psychotic.2 Every night, you and I mis-take the experience of dreaming for being awake and moving through the world as we normally do. We perceive the images of our minds no differently than we perceive the appearance of the physical world. (If that were to happen while you were awake, we'd call it a psychotic break.) You don't recognize a dream for what it is until you wake up. Makes us sound kind of crazy, right?

Dreams are at once the most private and the most universal part of the human experience. They are private in that every night you experience worlds that are simultaneously created by your own mind. They are universal in that every human dreams every night. Dreams are not something to be dismissed, and they are not to be touted as "otherworldly" or "revelatory" either; dreams are the most accessible mystery in phenomenological life. There are two extremes that I see in response to dreams, and I'll chart the middle path between them. These extreme perspectives come from two main camps. There are (1) the realists, empiricists, and materialists (hereafter "R/E/Ms", for fun) who regard dreams as useless hallucinations that we ought to ignore for being "not real." And then there are (2) the extra spiritual and mystical types (hereafter "S&Ms" — again, for fun) who treat dreams as premonitions or messages from beyond. Both perspectives cause you to miss the true nature and value of dreams.

As I sit here now, I can recall the dream where I saw God kill Himself for sport, the dream where I talked to my late great-grandmother, the dream where I did a gainer out of a helicopter and landed on my feet, and the many dreams in which I have sat on the ocean floor and breathed underwater. I can recall all of these as if they are memories of my experience, because they are. All of those dream-experiences feel just as real and solid — or, more accurately, just as illusory and ephemeral — as the experience of my first home run, my high-school graduation, or tree-skiing in Breckenridge this past season. These are experiences I've had that would remain unconscious and forgotten if I were not aware of my dreams.

Throughout my life, dreams have served as prompts for introspection, helping me dive inwards and breach with new self-knowledge, reducing the barrier between my conscious and unconscious mind to a translucent membrane. We tend to spend our days seeking progress and grasping after material things in the world, and we treat sleep as if it exists to renew our energy so that we can continue that grasping tomorrow. But when we treat sleep this way, we are overlooking (or under-seeking) this beautiful, immaterial part of our inner worlds: dreams. The most important work we do for ourselves doesn't happen 9–5. It happens as we sleep and dream. Don't you want to know what you're doing on your night shift?

Dear S&Ms: Dreams Are Prompts, Not Premonitions

A decade ago, I started a dream journal to prove that I was dreaming events that would happen in the future. On the first day of high-school, I had an intense feeling during roll call in biology that I had already dreamt the exact situation. As the teacher called out a new girl's name, I was convinced that I already knew her name and that I'd already seen her in my dream. At that time, my dream journal was new, and I flipped through the few entries for the dream I knew I'd had about biology class. It was nowhere in there.

That was the end of my spirituality-and-mysticism streak; I had debunked my supernatural powers with this experiment. And if you're into S&M, beware of this trap. Dreams are not messages from beyond but merely images from beneath.

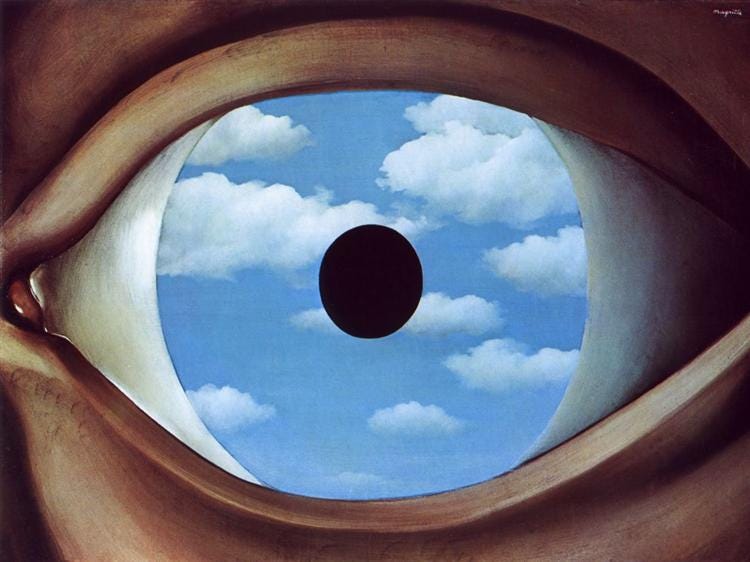

Dreams appear like an ink blot splatting on a page or like a cloud forming in the sky. There is no buried meaning to uncover; there is only meaning to ascribe. What do you see in the ink blot? If you want to really learn from your dreams, consider the unconscious dream content in the context of your conscious experience. By that, I mean, don't look up "being chased" in a dream-symbol dictionary. You won't learn anything about yourself. Instead, try to recall how it felt to be chased in that dream. What or whom were you running from? Were you trying to reach something or someone ? Did you make it there? How did the dream resolve itself, if at all? How does that scene relate to your waking experience at that time in your life? Interpreting a dream is not like reading a message from a bottle. It's more like seeing your face through a fun-house mirror and trying to read your expression — meanwhile, the glass is melting.

Imagine chartering a helicopter after a thunderstorm hoping to reach out the window with a waffle cone and scoop up some of the rainbow. That's how fruitless it is to search for meaning in a dream. The contents of a dream — the objects, the setting, the people — are not what matter about the dream. I wish I'd have realized this sooner; I've spent too much time and too many words writing about dream-content. There is no meaning to discover there. Dreams are as empty as a rainbow; they are bright, enchanting, fleeting images. You can't retrieve anything from something that is empty, but you can fill it. Fill it with meaning.

When you recall a dream, focus on the meta-content, and ascribe meaning to the dream by relating it to your conscious experience. How vivid was the dream, how long, how deep? What were the conceptual themes? What might the characters represent, archetypally, in your life? Was the scene comforting and safe, exciting and unfamiliar, or scary? What problem from your waking life might you be working through with this dream? Instead of trying to scoop up a little part of the rainbow, just stand back and focus on how the whole thing makes you feel. Let the dream give you a felt sense for the mood of your mind.

For instance, I had a streak of dreams set underwater around the time I was grieving the loss of a dear family member. These were not drowning dreams but peaceful, energizing dreams filled with gratitude, where I sat alone in the silent, dark depths. I reflected on this and ascribed to the dreams this meaning: I am comfortable with uncertainty and have an earnest desire to confront the inevitability of death. These dreams were not fearful. It was a signal that I wasn't running from the unknown but facing it. My interpretation made sense in context, because my grieving process for this loss had been the most healthy way I had ever dealt with death.

I've been dream-journaling for a decade now, and I've written more words about my dreams than about anything else — probably a few novels' worth by now. Not once have I ever recorded a dream that predicted the future. Now, I dream-journal for an entirely different reason than why I started. I treat dreams not as premonitions but as prompts for introspection.

Dear R/E/Ms: Where Is the Matter?

To all the realists, empiricists, and materialists out there, are you still with me? We've discussed how dreams can help you understand yourself. Now, let's consider how a careful attention to your dreams can change your perspective on the world.

You might consider yourself a R/E/M and tout the scientific method and take pride in only believing what you can see. Well, that's the same for me. I pride myself on being rational and analytical and skeptical and measured and discerning. I operate like you R/E/Ms; I too "have to see it to believe it." But I'm asking different questions, like "What am I to believe about what I see in my dreams?" A R/E/M might say that we are not seeing in our dreams but just "visualizing" or "imagining." Well, then why — every night — do we mistake our "visualizing" or "imagining" for seeing? If dreams are so distinct from "physical reality," why is our sensory (read: phenomenological) experience the same for both?

The dream you don't remember from last night is an example of something that exists that you cannot see. It happened, but you don't know what happened because you were unconscious to it. It's literally like blacking out from intoxication and failing to remember what you saw, said, and did the night before. We do this every night in non-lucid dreams (these are the vast majority of dreams, during which we are not aware that we are dreaming). We become unconscious to our experience. Rather than dismissing dreams as "not real," let's ask: What do dreams reveal about reality?

I'm all for being grounded and empirical, but see how that holds up the moment you become lucid in a dream and start flying high above a dreamscape that you're simultaneously and imperceptibly rendering with your mind. You have a stark moment of realization: I am dreaming. This is a dream. And then you leap from the ground and into the sky, for in a dream you have the ability to fly. Let's consider how the seemingly solid, lasting, and independent nature of "reality" unravels during this experience, down the R/E/M line:

The realist will cling to something like "I am dreaming. This is just a playground in my mind, not objective reality."

The empiricist struggles a little more and soaks up the data: "I'm experiencing the sensation of flight, but I'm aware that my physical body is literally prone and paralyzed in my bed. And moments ago, all the sensory evidence indicated that I was awake already. Only now do I recognize I am dreaming."

The materialist has to disregard the experience altogether, though they might enjoy it: "These images and feelings are the result of complex neural activities, activating certain pathways and a series of synapses that have merely replicated my senses in my imagination."

Realism, empiricism, and materialism hold here, but they're stretched beyond their normal applications. All they can do is contrast this experience with "objective reality" or describe the sensations or discount the experience as non-sensory. But it's worth asking: In this lucid dream, where is the matter? Where is the ground that you pushed off to start flying? Where are the molecules in the air causing the force of drag that blows back your hair? Where is your body? Where is the dreamer?

A careful look at dreams can throw a wrench in most epistemological and ontological perspectives. And that's the beauty of it! This is another benefit of engaging with your dreams: the more you attend to the worlds created by your mind, the more you realize how similar your dreaming and waking experiences are. Maybe this world, the one we all share, is made up of mind (is from mind) in the same way that a dream is. Even if you don't come to the conclusion that the waking world is dream-like, you will at least develop a healthy skepticism toward any dogmatic beliefs about the solid, lasting, and independent nature of reality.3

A R/E/M clings to the idea that what they know to be true are facts, citing science and rationality and empirical evidence. Dreams make you open to faith. You start to realize that everywhere, every day we are operating on the unverifiable belief that this is "reality" and that a dream. Every night we fail to recognize our dreams for what they are, so how do we know we aren't failing to recognize "reality" for what it is? Where is the empirical evidence that this is not another dream?4

Why to Start a Dream Journal

Every night, we set ourselves adrift at sea, floating blindly on our backs above the dark, formless parts of our minds. To not recall your dreams is to remain on your back — blind, blacked-out, disconnected from the deepest parts of you. Look down. Dream-journaling gives you the awareness of a snorkeler observing the contents of another world. Dive inwards. When you reflect on your dreams, you can see them in more vivid detail and relate them to your conscious experience, like the snorkeler kicking down to peer into the hole-home of an eel.

Dreams are the most accessible mystery in life, and if you investigate them, you will be rewarded with deep insights. And if you're at all interested in learning from your dreams, the first step is to start a dream journal.5 Since dreams are private, you will come to know yourself better by witnessing your unconscious. And since dreams are universal, you will come to understand the world better by relating to it from the shared nature of mind. Also, the more you dream-journal, the more you will remember your dreams, in both depth and frequency. It will also help you have lucid dreams.6

And if you need more convincing, here's one more point: the more I've dream-journaled, the fewer nightmares I've had. If you address and integrate the dark parts of yourself that take refuge in the unconscious, if you face your fears, then your shadows get lighter. Your unconscious stops lashing out at you when you fall asleep, because you become more attuned with your mind — and what a gift that is!

Fear, and the hesitation born from it, smothers life so that it burns at a pilot-light level. Things are safe, but semi-dead. […] On a spiritual level, fear is what keeps us from waking up. This is mostly our fear of the dark. Darkness represents the unknown, or the unconscious. We're always afraid of what we don't know or can't see. – Andrew Holecek, Dream Yoga7

To go through life without recalling your dreams is like exploring Earth without ever dipping your head underwater and opening your eyes. That's all I'm suggesting you do. In the morning, before leaping out into the arena of the world, look down, into yourself — even if it stings — and see what bubbles up from your unconscious. You have these wild experiences every night. You just don't remember them because you have no intention to recall them. Dream-journaling is the practice of escorting your unconscious experiences into your conscious memory for the joy of self-understanding (and self-detachment, but that's a topic for another time).

Tonight, you will have many dreams. Tonight, you will have good dreams. Tonight, you will remember your dreams.

Springboard

A carefully crafted question to help you dive inwards:

You don't have to wait to start your dream journal. Your first entry (or your next entry if you already have one) can be a dream you remember from your past. You can start your dream journal right now.

What is an impactful, memorable dream of yours, whether from this week or from your childhood? What does it indicate about the mood of your mind at that time, and what meaning do you ascribe to it?

Thank you for reading,

Garrett Kincaid

P.S. Every month, I publishing my fleeting thoughts and half-epiphanies as "logs" on my site. If you're curious, you can read a curated feed of my inner monologue. My site also serves as a curated library of my best thinking and writing.

Courtship with the Moon Incarnate

An excerpt from my dream journal, with my interpretation of its meaning

That is, unless you had a lucid dream. And even then, you almost certainly had other dreams last night that were non-lucid.

Definition of psychosis from The National Institute of Mental Health: "Psychosis refers to a collection of symptoms that affect the mind, where there has been some loss of contact with reality. During an episode of psychosis, a person’s thoughts and perceptions are disrupted and they may have difficulty recognizing what is real and what is not." It means mistaking the contents of your mind for reality, which we do every night.

Andrew Holecek playfully refers to "solid, lasting, and independent" as "The Unholy Trinity," for that is the lie that we keep telling ourselves about reality. It's actually fluid, fleeting, and relative — like a dream.

I have one last question for anyone who identifies as a materialist: how are you able to see in your dreams? (As we've established, your brain perceives no difference between the sensation of seeing a dream-scene and that of seeing while awake.) The objects of the waking world are illuminated by the bright light of our celestial, perpetual fusion bomb. So, what is the light source that illuminates the objects and scenes of your dreams? I'd like to offer that it is nothing material, that it is the primordial light of mind. (This answer is paraphrased from the words of Andrew Holecek.)

If you don't want to write, you can still have a dream journal. You could, instead, record your dreams as audio or dictate them to a speech-to-text tool. I personally hand-write my dream journal entries on an e-ink tablet (no backlight).

During my peak streaks of dream-journaling, which have numbered up to two or three weeks of writing 300+ words per day, I have had mornings where I'll recall five dreams at once. I'd remember the dreams from my 1:00 am REM cycle and the one at 3:00 am and 6:00 am, and they'd all come flooding into my memory when I'd wake up at 7:00. There have been many mornings where I've spent over an hour writing about one dream, writing more than 1,000 words about its vivid images, the narrative, its themes, and its significance to me.

This comes from Andrew's book Dream Yoga, and he has also inspired other ideas in this piece. I recently attended one of Andrew's dream yoga retreats in Colorado, and the experience spurred me to finally start writing about dreams. I'm grateful to have found Andrew's work, and I admire his writing. If you're curious, start here: "Lucid Dreaming vs. Dream Yoga: What's the Difference?".

This slaps

Great article. I look forward to restarting my dream journal with new ideas on how to think and reflect on my dreams this time around.